FROM REJECTION TO PROTECTION: THE PERILOUS LIFE AND TIMES OF NORTH AMERICAN BIRDS OF PREY

By Elizabeth Stoakes, BAS Historian

If asked, most modern people (and definitely birders) would say that they admire birds of prey. We enjoy their beauty and strength, revere their superb hunting skills and respect their roles in our ecosystem, keeping prey animal populations in check. However, this is a relatively new attitude towards raptors. Historically these birds were branded as “pests” and “villains” because some killed poultry and game birds coveted by hunters and farmers—who often overlooked the fact that raptors provided important rodent control as well. Raptors were hunted mercilessly and in huge numbers, regardless of the season, and their numbers were greatly diminished. Examination of some volumes in our collection bears witness to this tragedy, but also (thankfully) to the efforts of scientists to discover the truth about the natural history of birds of prey and spawn the love and appreciation for them which would ultimately lead to their protection.

The characterization of raptors as ruthless killers originated with the earliest ornithologists. Even John James Audubon described Great Horned Owls as “dangerous and powerful marauders…I have known a plantation almost stripped of the whole of the poultry raised upon it during spring, by one of these daring foes of the feathered race, in the course of the ensuing winter”1 (pg. 316; italics mine). As for the Red-tailed Hawk, he noted that mammals, frogs, snakes, etc. constituted much of its diet, but still could not resist giving a graphic description of its ongoing conflicts with farmers:

“As soon as the little Kingbird has raised its brood…the Red-tailed Hawk visits the Farm-Houses, to pay his regards to the poultry…sailing over the yard, where the chickens, the ducklings, and the young turkeys are, the Hawk plunges upon any one of them, and sweeps it off to the nearest wood…the farmer at the plough swears vengeance upon the robber…his rifle is raised to his shoulder in an instant, and the next moment the whizzing ball has pierced the heart of the Red-tailed Hawk, which falls unheeded to the earth…[during nesting] they seem to kill everything, fit for food, that comes in their way…amongst the American farmers the common name of our present bird is the Hen-Hawk…”1 (pgs. 266-270)

Unfortunately this nickname (and “chicken hawk”) and reputation persisted for generations, and was even applied indiscriminately to other raptor species, such as the Red-shouldered Hawk.

Part of the wholesale slaughter of birds of prey can be attributed to the 19th-century craze for collecting eggs, bird skins and taxidermy mounts. Some augmented scientific collections, but many more went to laypeople. A number of ornithologists of the time made their living primarily as hunters and taxidermists—such as John Krider, for whom the Krider’s Hawk is named10. In his succinct 1879 book, Forty Years Notes of a Field Ornithologist: Giving a Description of All Birds Killed and Prepared by Him, we find that as with many “gunners” of the day, Krider thought nothing of collecting 50 Red-tailed Hawks in a single hunting season, or of collecting whole clutches of eggs and pairs of breeding birds8. As with Passenger Pigeons, the raptor population was treated as though it were inexhaustible:

“From time to time Dr. Miller [of the American Museum of Natural History] received a parcel of hawk skins for the museum from his friend Justus Von Lengerke, whose favorite pastime was hawk-shooting from a strategic stand in the Kittatinny Ridge of northern New Jersey. Von Lengerke, who was something of an ornithologist, enjoyed his sport for many years and his kill must have been enormous.”5 (pg. 6)

During the same period, the insatiable demand by milliners for birds and their feathers to adorn ladies’ hats did not spare the raptors. Author Neltje Blanchan described seeing a woman at a New York Audubon Society meeting in 1898 wearing “the entire plumage of a saw-whet owl spread over her turban”4(pg. 343)! She also wrote that “Because it is small enough to crowd on a woman’s hat, this [saw-whet owl] is a little victim commonly worn, sometimes with wings and tail outspread, or again with only its head, like a Cheshire cat’s, appearing in a cloud of trimming”4(pg. 342).

In 1875, Delaware became the first state to enact a bounty on hawks and owls (omitting only Ospreys and Barn Owls), followed rapidly by Colorado, Virginia, West Virginia, New Hampshire, Ohio and Indiana. Prices paid ranged from 20 to 50 cents per bird, except in Indiana (which offered up to $2 each, sparing only Screech Owls and Kestrels)9. One of the worst laws was Pennsylvania’s “Scalp Act” of 1885 that declared war on mammalian predators as well as birds of prey. In the 18 months of the law’s existence, over 128,000 predators were killed7. An 1899 United States Department of Agriculture report noted that farmers in Pennsylvania typically lost approximately 5,000 poultry yearly to birds of prey, and each bird was worth around 25 cents. Therefore, the state of Pennsylvania had paid $90,000 in bounty money to save its farmers from a total loss of less than $2,0007! This fiscal irresponsibility led to the reversal of the law, and by 1890 many state bounty laws against raptors were abandoned. By 1899, eight states had actually begun to enact laws for the protection of at least some species of birds of prey9.

Some credit for these progressive laws must go to the work of the American Ornithologist’s Union (AOU), formed in 1883 to unite scientists in their efforts to understand the natural histories of all North American birds. Its members even successfully petitioned Congress for money to develop a division of “economic ornithology” within the Department of Agriculture, whose scientists would study the costs and benefits of wild birds’ natural activities especially to farmers and horticulturists9. (Later this department became the Division of Biological Survey—and still later, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.) A.K. Fisher, in his 1907 report Hawks and Owls from the Standpoint of the Farmer, protested the lack of understanding that was at the root of ongoing extermination of raptors:

“The ill feeling has become so deep rooted that it is instinctive even in those who have never seen hawk or owl commit an overt act [of predation on domestic animals]…How often are the services rendered to man misunderstood through ignorance! The birds of prey, the majority of which labor day and night to destroy the enemies of the husbandman, are persecuted unceasingly, while that most destructive mammal the house cat is petted and fed and securely sheltered to spread destruction among the feathered tribe…only 3 or 4 birds of prey hunt birds when they can procure rodents for food…It is to be regretted that the members of the legislative committees who draft state game laws are not better acquainted with the life histories of raptorial birds. It is surprising also that gun clubs should be so far behind the times as to offer prizes to members who kill the greatest number of birds of prey…already the leading agricultural papers and sportsmen’s journals are deprecating the indiscriminate slaughter of these useful birds…”6 (pgs. 1-2).

This report described each species separately and gave detailed descriptions of their diets (obtained by examining numerous stomachs of dead birds). For example, 66% of all the food found in Red-tailed Hawks consisted of rodents, with very few birds of any kind—though many were still shot on sight as presumptive chicken thieves. Fisher’s report was valuable for publicizing the beneficial activities of raptors, but he still clung to the prevailing view that some birds of prey were “good” and worthy of protection (any bird that ate mainly rodents was “good”), and others “harmful” (any predator mostly of birds). A bird’s value was based solely on what it could do or not do for humans. To his credit, Fisher did point out that many raptors supplemented their diets by consuming large numbers of insects, another service to the farmers—and also that most birds only resorted to eating poultry when other food was scarce, as in winter, or when they were nesting and needed large quantities of food for their young6.

While most raptors were gaining a measure of grudging respect as the 20th century began, Cooper’s and Sharp-shinned Hawks, Northern Goshawks, and Great Horned Owls continued to be almost universally reviled as “enemies” not only of farmers, but of the bird community in general. Naturalists were not immune to these prejudices and ambivalent attitudes. In her 1904 book, Birds That Hunt and Are Hunted, Neltje Blanchan called herself a “bird-lover” who believed that “To really know the birds in their home life, how marvelously clever they are…cannot but increase our respect for them to such a point that wilful injury becomes impossible” (pg. ix, italics mine). She also rhapsodized eloquently about the need for “public sentiment against the wanton destruction of bird life for any purpose whatsoever” (ibid). She noted that farmers in Pennsylvania had recently experienced a plague of mouse damage to crops, largely because they had foolishly eliminated many of the local owls. “Nature adjusts her balances so wisely that we cannot afford to tamper with them”, she righteously concluded (ibid). So it is all the more shocking when, some pages later, she has no compunction about describing the Sharp-shin as a “destructive little reprobate” and “marauder” that “often escape(s) the charge of shot they so richly deserve” (pg. 313). Even worse, she declares that the Cooper’s Hawk “lives by devouring birds of so much greater value than itself that the law of survival of the fittest should be enforced by lead until these villains…adorn museum cases only” (pgs. 314-15, italics mine)! She also characterized Goshawks as “the most destructive creature on wings” and “Bloodthirsty, delighting in killing what it often cannot eat…” (pgs. 315-16). Great Horned Owls were referred to as “lord high executioner of the owl tribe” that “does more damage than all other [owl] species put together…song birds do not escape the stealthy murderer that picks them from the perch as they sleep; and all the rats, mice, squirrels, rabbits, and other mammals eaten cannot offset the valuable birds destroyed” (pgs. 345-46). Finally, she repeated these same sentiments (in milder, less dramatic form) in her 1910 bird book for children (Birds Every Child Should Know), thus creating yet another generation of raptor-hating “bird lovers”.

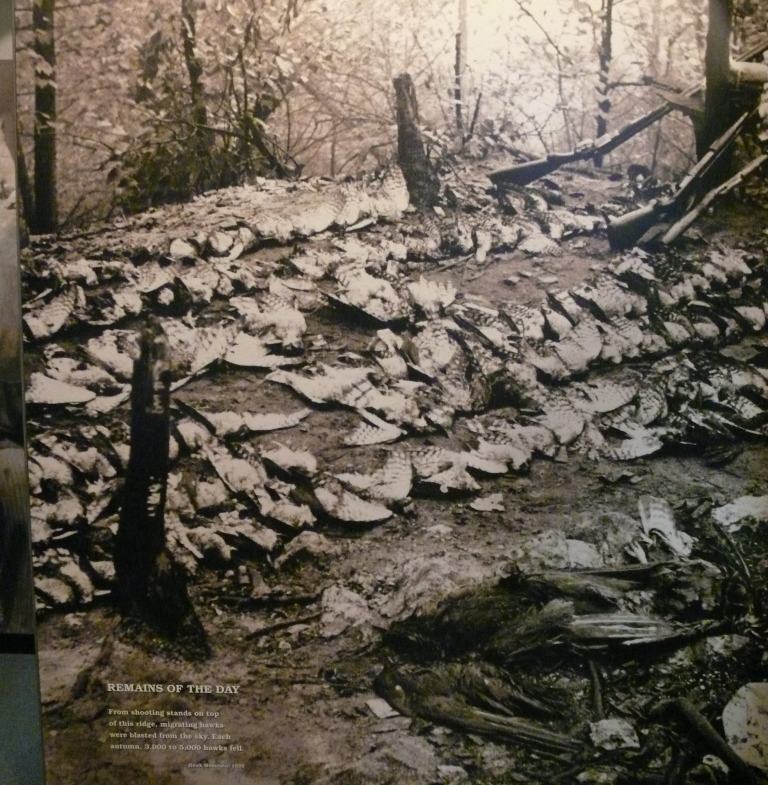

Richard Pough’s photographs exposed the hawk slaughter to public view. 1932.

By the early 1900s, members of the early Audubon societies began to be alarmed by the enormous and accelerating loss of birds to indiscriminate hunting. The federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) of 1918 helped stem the loss of game birds and song birds but did not necessarily protect birds of prey. Longstanding local laws and customs often prevailed. In 1929 the Pennsylvania Game Commission revived its bird bounty law, offering $5 for every Goshawk and Great Horned Owl that was killed—a substantial sum during the Great Depression. The law persisted until the early 1960s and records show that between the years 1947 and 1962, 1,000 to 2,000 Great Horned Owls were collected annually—a total loss of 16,000 to 32,000 birds7.

Hunters often could not identify different types of hawks in the field and did not care; they reflexively shot any bird of prey they encountered. One of the most popular hunting areas in eastern Pennsylvania came to be called “Hawk Mountain”. Some of the resulting devastation can be seen in the accompanying photographs. Publicity generated by horrified birders brought the slaughter to the public’s attention and eventually led to the creation of the world’s first raptor sanctuary, which still stands today. Rosalie Edge purchased the property in 1934 and employed caretakers, determined to give the hawks at least one zone of safety. The waves of migrating raptors have been counted every autumn since 1946 and the site has provided invaluable information about their populations. A more complete history can be found in The View from Hawk Mountain (1973) and in Hawks Aloft (1949), the latter written by Maurice Broun, one of Hawk Mountain’s original wardens. Broun revealed that in those early days he could not even rely on local law enforcement personnel to help him confront the trespassing hunters—the deputies themselves had been enthusiastic participants in the autumn ritual. He went on to describe how newspapers publicized and glorified the hunts, drawing even more shooters to the ridges:

“Mankind in general seemed bent on the extinction of birds of prey…Late in 1932, I learned about the graveyard of hawks at Drehersville, in east central Pennsylvania…Blue Mountain is a long continuous ridge along which thousands of hawks pass in migration. First the Broad-wings in September…then come the Sharp-shins and Cooper’s Hawks—thousands of these were killed…When 100 or 150 men, armed with pump guns, automatics and double-barreled shotguns are sitting on top of a mountain looking for a target, no bird is safe…Hawk shooting campaigns were being urged by trigger-happy sportsmen throughout the country, reacting to propaganda to annihilate our hawks and owls issued by gun and ammunition makers…”5(pgs. 4-5)

Although shooters could no longer utilize the ideal vantage point of Hawk Mountain, unregulated raptor hunting continued well into the 1950s. As late as 1971, over 700 Golden Eagles were slaughtered from airplanes by sheep ranchers in the West ostensibly concerned about protecting their free-ranging lambs7.

Sadly bullets were not the only source of danger. Some poultry and game bird farmers resorted to setting muskrat traps on top of fence posts and tree snags to snare hawks and owls hunting near their birds—resulting in prolonged suffering and cruel death3.

Otto Widmann (a founding member of the Audubon Society of Missouri) noted in 1907 that laws alone were useless for protecting birds of prey, unless the public could be made to understand the necessity of these regulations:

“In Missouri, in spite of all persecution, [the Barred Owl is] still a fairly common resident in all portions of the State, mainly in the heavy timber of the river bottoms, where there are natural cavities in tall trees, particularly sycamores, in which it can hide and nest. Unlike all other owls, it is often heard to hoot and laugh during the daytime, betraying its whereabouts to the hunter, who deems it his duty to go for it and try to kill it. With all other owls, except the Great Horned Owl, the Hoot Owl is now protected by the new game law of Missouri, but as long as the population is not educated enough to understand and appreciate such a law…no law will save the hawks and owls from being killed whenever opportunity offers. The slow process of elucidation through nature study in the schools is the only hope that in the course of time bird protection laws will receive that measure of sympathy which is necessary for their enforcement.”11(pg. 107)

As for the persecution of Great Horned Owls, Widmann dryly remarked:

“No one contradicts the often repeated statement, that this powerful bird of prey is destructive to poultry, but…if the farmer would take proper care of his fowl and keep them at night where they belong and not in the open all winter, there would be little loss through his owlship’s faults”11(pg. 110).

As industrialization and development rapidly occurred after World War II, raptor populations faced new hazards from pesticides and loss of habitat. In the 1960s and ‘70s, some pessimists were convinced that even our most common birds of prey might soon be lost forever. This concern was perfectly understandable, when we remember that Bald Eagle and Peregrine Falcon populations had drastically plunged by this time; the Endangered Species Act (ESA) was still to be written; Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) had awakened people to the dangers of chemical pollution, but the ban on DDT also lay in the future—and some feared it would come too late to save not only birds, but humans. This view was expressed in books such as The World of the Red-tailed Hawk, written in 1964 by G. Ronald Austing:

“If in the wake of our ever-exploding civilization we cannot somehow manage to save enough acreage to sustain a satisfactory number of stable pairs, the extirpation of redtails from vast sections of their present range is inevitable. Even today, as its numbers steadily decline, many of us are naïve enough to take the redtail for granted. The species itself appears sufficiently adaptable to escape total extermination in the future, but its numbers will continue to decline as our own population increases. The day is fast approaching when the redtail will be absent from the daily checklists of amateur bird watchers.”2(pgs. 11-12)

Fortunately his dire predictions did not materialize and now this bird—along with Cooper’s Hawks, Red-shouldered Hawks, Great Horned Owls, and Barred Owls–has in fact adapted well to living near humans and is currently thriving and commonly seen. Austin’s photographs and loving descriptions of the hawks and their way of life helped to educate the public and inspire an appreciation of our birds of prey which persists today.

Conditions for raptors improved slowly but steadily. The year 1972 saw not only the banning of DDT and passage of the ESA, but a signing of the first treaty between the United States and Mexico designed specifically to protect birds of prey7. The first “Eagle Days” celebrations began in a few states (Kentucky, Tennessee, and Missouri) to educate the public about our national bird and the progress of its recovery from near-extirpation. Eagles have recovered within my lifetime—a big thrill for a birder. In the year I was born, 1965, the number of Bald Eagles in the lower 48 states was estimated at only 1000—now Missouri regularly harbors one of the largest wintering populations of eagles outside of Alaska and the total for the lower 48 is approximately 20,000 birds (according to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service data).

So why revisit this grotesque early history of wanton waste and slaughter, which most birders would just as soon forget? Because I agree with Mr. Austing, that we should never, ever take our birds of prey “for granted”! It is nothing less than a miracle that they survived several centuries of persecution, years of a “war on nature” when they were considered enemies fit only for target practice. But they still require our vigilance and our protection–now more than ever. According to the American Bird Conservancy, wind turbines unwisely placed in heavily used migration corridors kill hundreds of raptors each year—as ruthlessly as the flying bullets on Hawk Mountain once did. Lead shot used to hunt waterfowl still poisons many eagles as they feed on dead and dying birds. Carelessly used rodenticides also cause secondary poisoning to rodent-eating raptors. High-voltage power lines and towers claim birds with electrocution and collisions. Worst of all, sprawling human habitation continues to steadily consume the remaining living space and disrupt the breeding cycles of those birds of prey that choose to live, and deserve to live, peacefully, far from our noise, pollution and constant activity. Many problems remain to be solved in order to keep them with us forever.

I hope that everyone who sees or hears a hawk or an owl today will appreciate them even more, knowing that they very well could have been driven to extinction if birders, scientists and others who cared for them had not intervened. Not just the brave keepers of Hawk Mountain and other refuges, but people like Scott Weidensaul, who established Project Snowstorm to study Snowy Owls. The conservation agents and falconers who bred endangered Peregrine Falcons in captivity and returned them to freedom in some of our cities. Volunteers who erect, maintain and monitor nest boxes for American Kestrels. Wildlife rehabilitators who nurse many injured raptors each year. Birders who spend days counting migrating raptors each spring and fall. Everyone can help. Observe birds of prey whenever you can. Learn as much as you can. Support legislation such as the MBTA and the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act that has helped to save raptors, and monitor conservation situations that affect raptors in your own state. (Just a few years ago, conservation groups here in Missouri joined forces to deter the building of a wind farm near Loess Bluffs National Wildlife Refuge, saving the lives of many migrating birds, including raptors.) Most important of all, share and perpetuate your love and respect for birds of prey with all the young people in your life to hopefully safeguard the future. You’ll be glad you did!

Please send comments and questions to Elizabeth Stoakes at lizkvet AT yahoo DOT com.

REFERENCES

- Audubon, John James. 1831. Ornithological Biography: Volume I. Neill & Company, Printers, Old Fishmarket, Edinburgh.

- Austing, G. Ronald. 1964. The World of the Red-tailed Hawk. B. Lippincott Co. Philadelphia and New York.

- Austing, G. Ronald. 1966. The World of the Great Horned Owl. B. Lippincott Co. Philadelphia and New York.

- Blanchan, Neltje. 1904. Birds That Hunt and Are Hunted: Life Histories of One Hundred and Seventy Birds of Prey, Game Birds and Water-fowls. Grosset & Dunlap, New York.

- Broun, Maurice. 1949. Hawks Aloft: The Story of Hawk Mountain. Dodd, Mead Co., New York.

- Fisher, A.K. July 18, 1907. Hawks and Owls From the Standpoint of the Farmer. United States Department of Agriculture Biological Survey, Circular No. 61.

- Heintzelman, Donald S. 1979. Hawks and Owls of North America: A Complete Guide to North American Birds of Prey. Universe Books, New York.

- Krider, John. 1879. Forty Years Notes of a Field Ornithologist: Giving A Description of All Birds Killed and Prepared by Him. Press of Joseph H. Weston, Philadelphia.

- Palmer, Theodore S. 1899. A Review of Economic Ornithology in the United States. Pages 259-292. Yearbook of the Department of Agriculture. United States Department of Agriculture.

- Trotter, Spencer. 1914. Some Old Philadelphia Bird Collectors and Taxidermists. Cassinia: Proceedings of the Delaware Valley Ornithological Club, No. XVIII. Philadelphia,

- Widmann, Otto. 1907. A Preliminary Catalog of the Birds of Missouri. Transactions of the Academy of Science of St. Louis, Vol. XVII, No. 1.

Very thorough and well written!

Maybe the awareness that is up for the Monarch will also help for the Birds of Prey. I do so hope we don’t lose protection for birds.

Were there Tales from the Library #1 and #2?

Yes.

https://burroughs.org/2017/01/tales-library-1-new-blog-burroughs-audubon-society/

https://burroughs.org/2017/01/tales-library-2-penguins-polar-expeditions/

Very well written. I enjoy all of your bird articles.